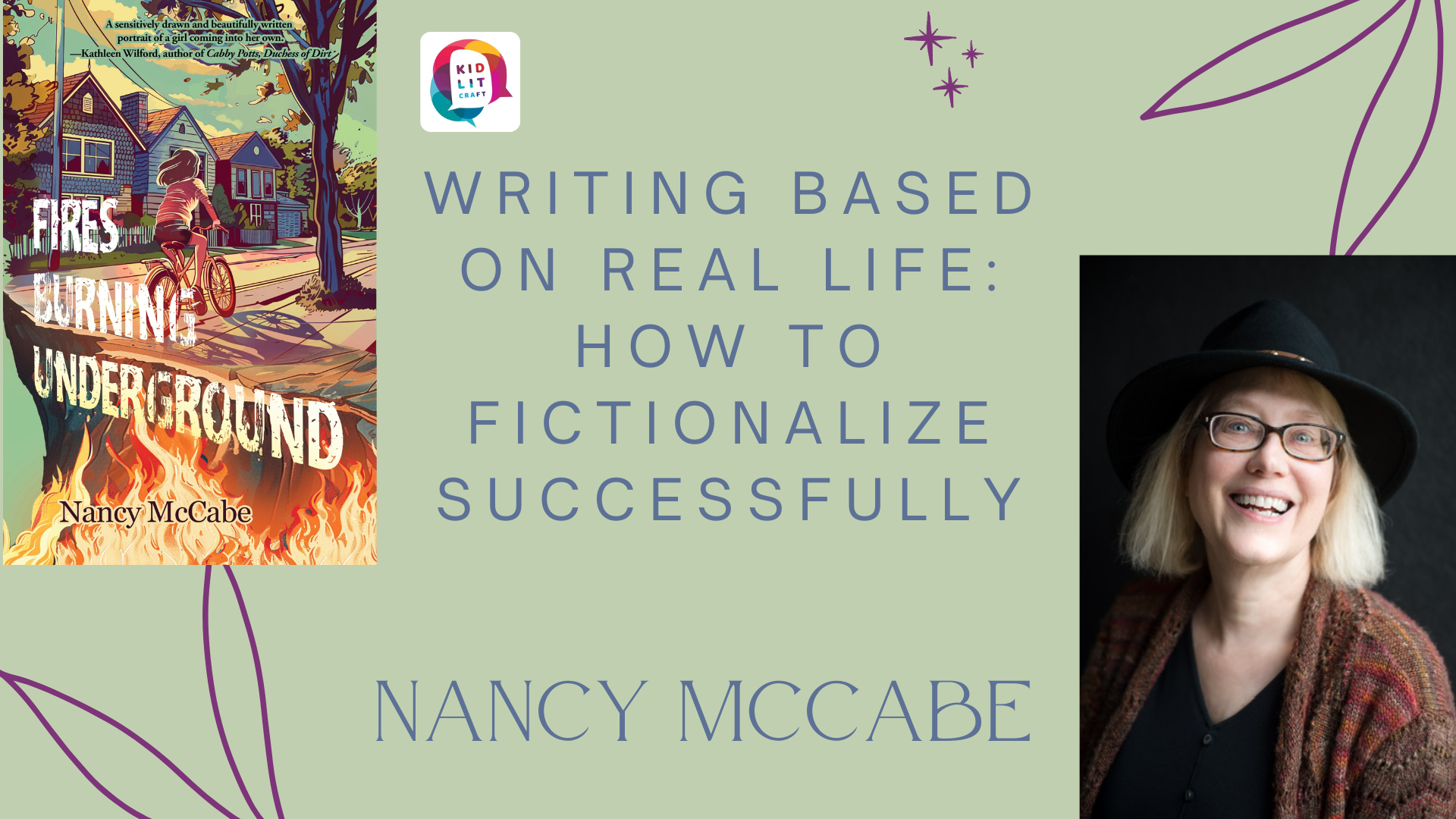

Writing Based on Real Life: How to Fictionalize Successfully

guest article by Nancy McCabe

The first draft of my new middle grade novel Fires Burning Underground was extremely popular with its intended audience—my daughter, then about nine. The story was also a memoir, for no reason other than I had written several memoirs and was still in that mindset.

As I revised my draft, I became more invested in it. I wanted to develop it for a broader audience. Gradually it became clear that my story would work better as a novel. Here are some things I learned about converting a personal story into fiction.

You not only don’t have to stick to what really happened, you probably shouldn’t.

I was so used to telling true stories, it took me a while to embrace the idea that I could make things up. Once I did, though, I found it freeing.

I kept some elements from my real life: the death of a Sunday school classmate in a fire when I was twelve, another housefire that happened only weeks later in my neighborhood, an intense friendship full of creative projects and schemes that allowed me to cling to my childhood a little longer, our experiments with the Ouija board that spooked me and gave me nightmares.

In real life, the Ouija Board experience was more funny than scary. It told my friend Marissa and I that we were sisters, born on the planet Leshma and then accidentally separated when sent to earth. Our parents were named Bene and Gruce Jactq, and we had sisters named Abigmxs and Icuagsclsurag. Our original Leshman names were Carla and Wendy.

While I was amused by these details, I decided that they weren’t serving my story. So I revamped all of the Ouija Board messages, making them more sinister, leading my main character Anny to worry that the boy who died is haunting her.

2. Unless the work needs to be historical, consider updating it for contemporary readers.

My story took place in the 1970s—fifty years ago. To a middle grade reader, that’s several lifetimes. There was no reason that my particular story needed to take place in an earlier time period, so I set out to see what would happen if I gave it a more contemporary setting. Conflicts came to life as I updated the story. I realized that the current political and social climate and Anny’s parents’ conservatism might lead them to homeschool. I realized that Anny would live in a world where many of her peers had cell phones and played video games, and some of these details could be woven in to enhance rather than detract from Anny’s fairly timeless concerns.

3. Change names from real life to help you conceive of the people in your story as characters and give you more leeway in developing them.

Changing my narrator’s name from Nancy to Anny helped me to conceive of her as someone with her own personality and voice apart from me. It’s easy to take ourselves for granted, so even in memoir it’s necessary to start thinking of ourselves as characters in order to communicate who we are. Thinking of Anny as a character, even if she borrows some aspects from my childhood self, forced me to see her more clearly and develop her more fully. This leads me to the next tip:

4. Create a distinctive voice for your narrator.

When I wrote the manuscript as a memoir, the voice was pretty much mine, an adult looking back on childhood. While there is certainly great value in listening to our elders, young readers are more interested in immersing themselves in stories about peers they can relate to. Finding Anny’s twelve-year-old voice didn’t mean that she had to use tons of slang or colloquialisms. It just meant that I needed to tune in to the way my daughter and her friends talk, revisit my own childhood diaries, and listen to the way the college students I teach, only a few years removed from childhood, speak and write.

I also found myself listening more to the kinds of things that preoccupied young people. When I was a child in the Midwest, we tended to assume that everyone came from the same cultural background and that everyone was white and cis and heterosexual and neurotypical. But my students and my daughter’s classmates were more explicitly interested in articulating the uniqueness of their backgrounds and identities. I particularly had to think about how Anny, as a contemporary child, would think about these issues, and that helped Anny’s conflicts really click into place.

5. Focus on bringing out the cause-and-effect elements of the plot.

When writing a personal story, we often instinctively structure it as a series of anecdotes or episodes, since we don’t tend to see our lives as unified stories. But plot in fiction is about cause and effect, how one event leads to another and then to another.

The inciting incident of my story is the death of Anny’s Sunday School classmate right before she leaves behind homeschool to attend public school. Both of these events highlight her longing for a best friend and raise questions about who she is and how her views of issues like religion and sexuality are going to shift in this new environment.

In addition, the friend’s death fuels Anny’s fears and nightmares as well as her desire to hang onto childhood a little longer rather than face the adult world. This leads to her and her new friend Larissa’s explorations of the supernatural and of creative projects—making up secret codes, creating a treasure hunt with rhyming clues for her oldest friend Ella, planning a backyard carnival. Anny’s longing to stay a child eventually blinds her to what’s happening with Larissa and causes her to neglect Ella. These things come to a head dramatically when Ella’s house catches fire.

As a result, the two fires, rather than being random events, are tightly woven together in the plot—and fiction allowed me to compress time so that many events in Anny’s life explode at once, rather than the way they happened over the course of several weeks in real life.

The Advantages of Fictionalizing

Overall, converting the story from real life to fiction made it more dramatic and thematically unified.

The process also enabled me to make many discoveries along the way. I got to know Anny better as a distinct person apart from me, and as I explored my characters and these events, I was surprised at how much better I came to understand my own experiences. In this case, converting my story from a personal one to a piece of fiction was the best choice. Not only did it strengthen the story I wanted to tell, but it reminded me that sometimes fiction is the best way to discover the truths of our lives.

Now it’s YOUR turn . . .

If you’re including events from your real life into your story, make sure to

Discover the ways your main character is different from you

Fit the events into the time setting of your story

Fudge time and details as much as you need to in order to serve your story

Consider how the events can strengthen the thematic structure of your story

Nancy McCabe is the author of nine books, most recently the middle grade novel Fires Burning Underground, the comic novel The Pamela Papers: A Mostly E-pistolary Story about Academic Pandemic Pandemonium, and the young adult novel Vaulting through Time. She has also published memoirs and award-winning essays for adult audiences. Her books have been finalists in the National Indie Excellence Award, the Eric Hoffer Award, the Montaigne Medal, the American Book Fest Best Book Award, and the Next Generation Indie Award. The Pamela Papers won the 2024 Next Generation Indie Award for humor/comedy.

Nancy directs the writing program at the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford and teaches creative nonfiction and fiction for the Spalding University Brief Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing.